More on Hospitals

Healthcare, a Human Right?

Health is wealth, the adage goes. Attributed to the Roman poet Virgil, it has endured over 2 millennia. In its simple framing, it nicely illustrates the vital importance of our health and wellbeing. But in the American modern age, it would seem that wealth is health - that only the sufficiently affluent people can afford good healthcare, while millions are going bankrupt due to medical debt [1, 2]. The recent government shutdown and the impending increase in health insurance premiums for millions of people has brought the plight of the public health concerns to the forefront.

In a previous essay, I pondered on the comparison of hospital beds in G8 countries, and showed the trend of steadily decreasing hospital beds per capita. Subsequently, curiosity got the better of me, and I did some digging on the number of total hospitals in the United States and how that has changed over time, given population and GDP growths.

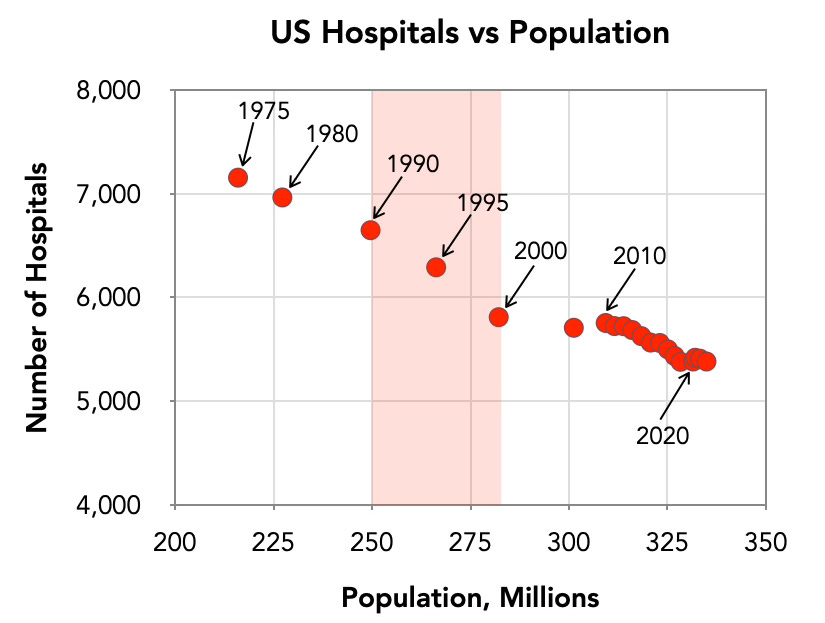

Figure 1 shows the number of total hospitals (federal and non-federal) in the US with the increase in population over the years, between 1975 and 2023. There is a 24.8% decrease in hospitals between 1975 and 2023, with a population increase of 55%.

This is very much counter-intuitive because the rate of hospitalizations has not decreased across decades - if anything, it has increased in the last 10 years, according to the CDC. The biggest change in hospital numbers happened in the 10 years between 1990 and 2000 - almost half the hospital closures in the last 50 years happened in that single decade alone.

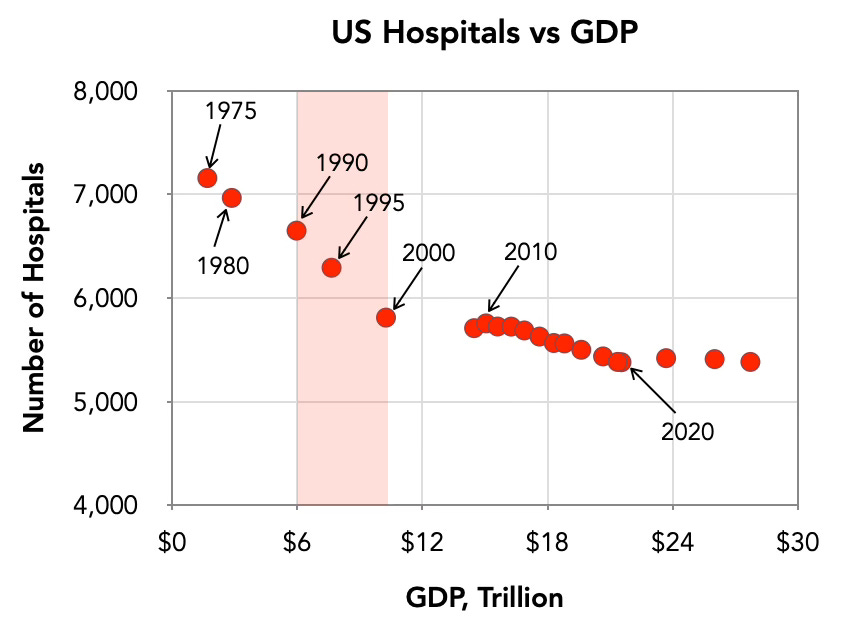

Figure 2 shows how the number of US hospitals changed with GDP. Basically, it indicates that while the GDP has been increasing, the number of hospitals have been decreasing. Since 1975, there has been a 16x increase in GDP.

So, with increasing population and, in a manner of speaking, national wealth, the US is showing a steady decrease in its healthcare capacity. Much research has been conducted on the hospital closures in America and the impacts, especially in rural areas [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. There are many nuances to issue, with aspects of insurance, cost, taxation, etc. that are all intertwined. However, I find it quite alarming in essence, for the biggest economy in the world to steadily reduce its hospital base, the healthcare capacity.

At the same time, we have the following facts to contend with: job growth and wages are stagnant, and the prices of basic goods are high and increasing significantly. My mind keeps coming back to Tunisia - a country where people were in a state of extreme social hardship from high inflation, high unemployment and poor healthcare infrastructure before the revolution that brought down the government in 2011.

Prior to that, in 2006, Ben Ali’s regime had initiated a 5-year plan to increase GDP, open the economy to foreign investments, reduce unemployment and many other lofty goals, most of which were not realized - unemployment rose, corruptions ran rampant with only the elites and regime-connected people availing themselves of the fruits of investments, and all forms of public dissent were very aggressively crushed. In the healthcare arena, even though a national health insurance program was initiated, it was in name only - the average household had to pay up to 45% of healthcare costs out of pocket. The low income families simply could not afford healthcare.

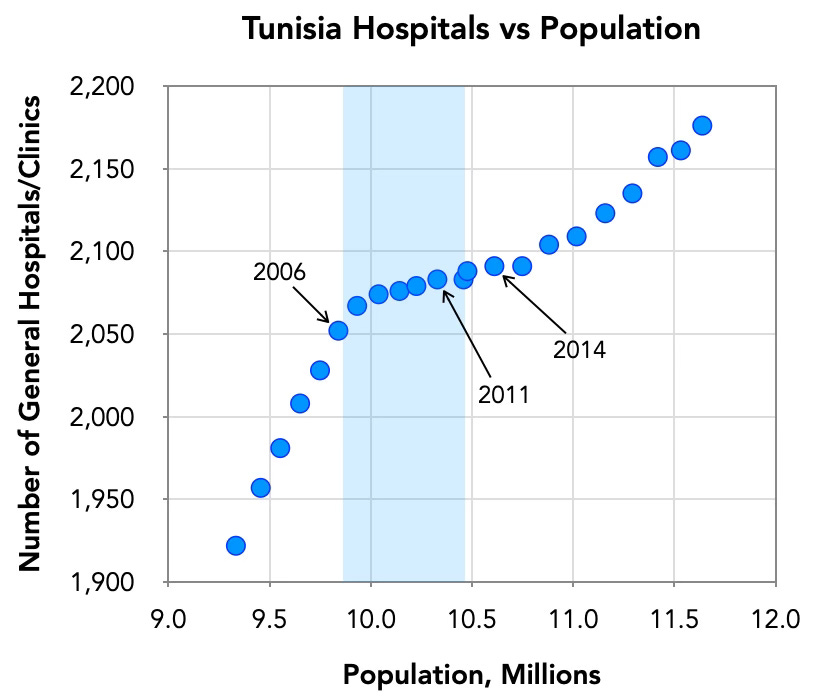

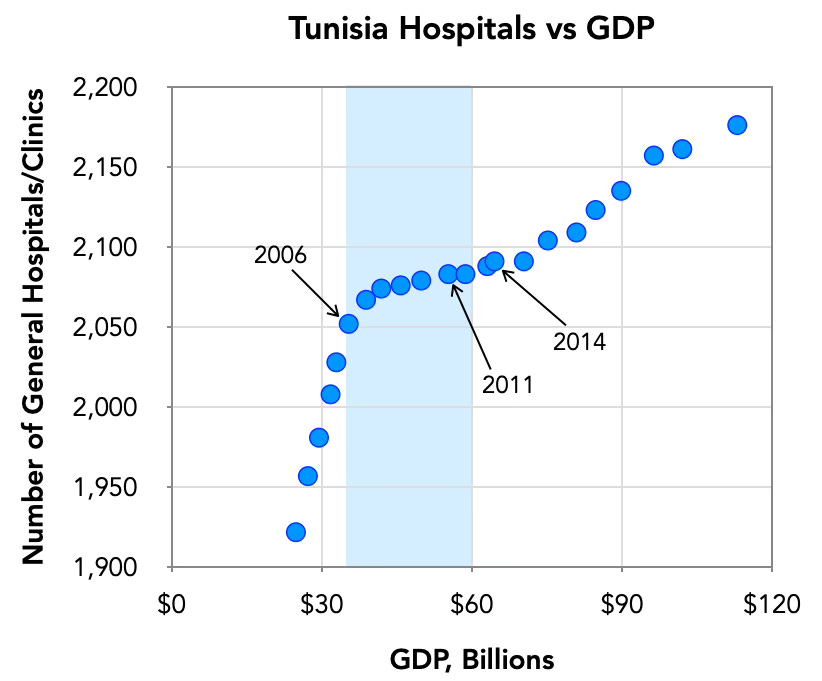

So, let’s take a look at the same hospital metrics for Tunisia. Figure 3 and 4 show the number of hospitals against population and GDP. During the 5 years between 2006 and 2011, the rate of hospital openings slowed down and became stagnant - a result of the complete lack of focus on healthcare in the 2006 5-year plan.

In 2011, after Ben Ali was forced to flee in the revolutions, the new Tunisia constitution established in 2014 recognized healthcare as a human right, and initiated programs to improve the health sector. This is evident in the subsequent increase in the number of hospitals with respect with both population and GDP.

(In light of this, how should we think about the overall US social spacetime? I’ll look for your thoughts in the comments.)

While Tunisia is often cited as an example how a small act of rebellion - the self-immolation of the street fruit-seller Mohamed Bouazizi - can bring down a whole government, it is the underlying parametric state of the society that makes it possible for the single perturbing spark to ignite the whole nation. As such, the past and its mathematical metrics are the breadcrumbs that we ought to explore further. An essay on this topic in the coming weeks…